But while some countries’ economies are already back to normal, others are lagging far behind.

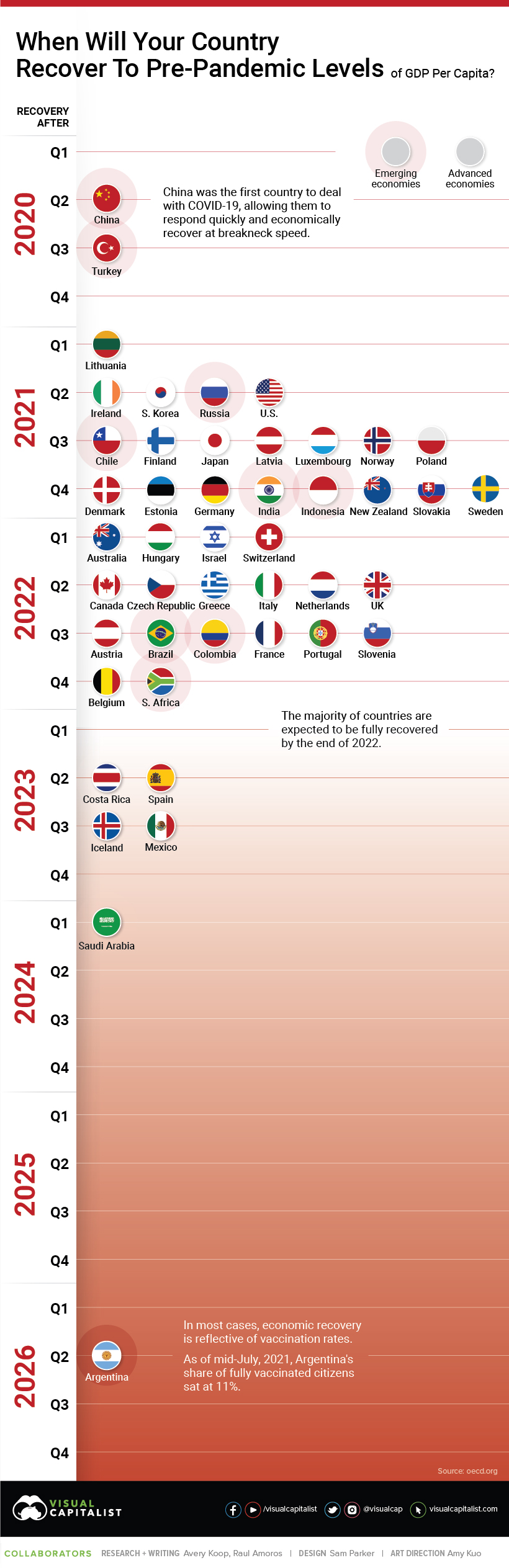

COVID-19 Recovery Timelines, by OECD Country

This chart using data from the OECD anticipates when countries will economically recover from the global pandemic, based on getting back to pre-pandemic levels of GDP per capita. Note: The categorization of ‘advanced’ or ‘emerging’ economy was determined by OECD standards.

The Leaders of the Pack

At the top, China and the U.S. are recovering at breakneck speed. In fact, recovering is the wrong word for China, as they reached pre-pandemic GDP per capita levels just after Q2’2020. On the other end, some countries are looking at years—not months—when it comes to their recovery date. Saudi Arabia isn’t expected to recover until after Q1’2024, and Argentina is estimated to have an even slower recovery, occurring only after Q2’2026. Most countries will hit pre-pandemic levels of GDP per capita by the end of 2022. The slowest recovering advanced economies—Iceland and Spain—aren’t expected to bounce back until 2023. Four emerging economies are speeding ahead, and are predicted to get back on their feet by the end of this year or slightly later (if they haven’t already):

🇷🇺 Russia: after Q2’2021 🇨🇱 Chile: after Q3’2021 🇮🇳 India: after Q4’2021 🇮🇩 Indonesia: after Q4’2021

However, no recovery is guaranteed, and many countries will continue face setbacks as waves of COVID-19 variants hit—India, for example, was battling its biggest wave as recently as May 2021.

Trailing Behind

Why are some countries recovering faster than others? One factor seems to be vaccination rates. As of July 16th, 2021. The higher the rate of vaccination, the harder it is for COVID-19 to spread. This gives countries a chance to loosen restrictions, let people get back to work and regular life, and fuel the economy. Additionally, the quicker vaccines are rolled out, the less time there is for variants to mutate. Another factor is the overall strength of a country’s healthcare infrastructure. More advanced economies often have more ICU capacity, more efficient dissemination of public health information, and, simply, more hospital staff. These traits help better handle the pandemic, with reduced cases, less restrictions, and a speedy recovery. Finally, the level of government support and fiscal stimulus injected into different economies has determined how swiftly they’ve recovered. Similar to the disparity in vaccine rollouts, there was a significant fiscal stimulus gap, especially during the heat of the pandemic.

Recovering to Normal?

Many experts and government leaders are now advocating for funneling more money into healthcare infrastructure and disease research preventatively. The increased funding now would help stop worldwide shut downs and needless loss of life in future. Time will tell when we return to “normal” everywhere, however, normal will likely never be the same. Many impacts of the global pandemic will stay with us over the long term. on Both figures surpassed analyst expectations by a wide margin, and in January, the unemployment rate hit a 53-year low of 3.4%. With the recent release of February’s numbers, unemployment is now reported at a slightly higher 3.6%. A low unemployment rate is a classic sign of a strong economy. However, as this visualization shows, unemployment often reaches a cyclical low point right before a recession materializes.

Reasons for the Trend

In an interview regarding the January jobs data, U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen made a bold statement: While there’s nothing wrong with this assessment, the trend we’ve highlighted suggests that Yellen may need to backtrack in the near future. So why do recessions tend to begin after unemployment bottoms out?

The Economic Cycle

The economic cycle refers to the economy’s natural tendency to fluctuate between periods of growth and recession. This can be thought of similarly to the four seasons in a year. An economy expands (spring), reaches a peak (summer), begins to contract (fall), then hits a trough (winter). With this in mind, it’s reasonable to assume that a cyclical low in the unemployment rate (peak employment) is simply a sign that the economy has reached a high point.

Monetary Policy

During periods of low unemployment, employers may have a harder time finding workers. This forces them to offer higher wages, which can contribute to inflation. For context, consider the labor shortage that emerged following the COVID-19 pandemic. We can see that U.S. wage growth (represented by a three-month moving average) has climbed substantially, and has held above 6% since March 2022. The Federal Reserve, whose mandate is to ensure price stability, will take measures to prevent inflation from climbing too far. In practice, this involves raising interest rates, which makes borrowing more expensive and dampens economic activity. Companies are less likely to expand, reducing investment and cutting jobs. Consumers, on the other hand, reduce the amount of large purchases they make. Because of these reactions, some believe that aggressive rate hikes by the Fed can either cause a recession, or make them worse. This is supported by recent research, which found that since 1950, central banks have been unable to slow inflation without a recession occurring shortly after.

Politicians Clash With Economists

The Fed has raised interest rates at an unprecedented pace since March 2022 to combat high inflation. More recently, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell warned that interest rates could be raised even higher than originally expected if inflation continues above target. Senator Elizabeth Warren expressed concern that this would cost Americans their jobs, and ultimately, cause a recession. Powell remains committed to bringing down inflation, but with the recent failures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank, some analysts believe there could be a pause coming in interest rate hikes. Editor’s note: just after publication of this article, it was confirmed that U.S. interest rates were hiked by 25 basis points (bps) by the Federal Reserve.